Finding Manuland I

How I discovered the M-N- Moon-based metaphorical signalling system lurking inside almost every sentence we speak, and what it means.

In October 2021 I was returning from my final vacation before my forced retirement from my beloved diplomatic posting to Ukraine.

I was driving through eastern France, towards the Belgian city of Mons, not far from Mainz in Germany. My route back eastwards, I had noticed, would bring me through Frankfurt-on-Main too!

Once I’d started detecting this pattern of similar sounding place names across so many different countries, I saw it everywhere I went. As I was crossing France, the word “Maing” popped up on my Satnav, like a troll. Of course, I clicked on it! There was almost no information about Maing. No hotel. No restaurant. No “attractions,” according to TripAdvisor.

“Another one of these Man- sounding towns!” My mind raced on, “Why do so many locales across the whole of Europe, Central Asia and India have names that sound mainly the same?!”

That was about the hundredth time I’d had that idea. I never took any action to satisfy my curiosity.

“What if… I visit this Maing. Will I see a sign there of what connects Maing to all the other places I’ve been with similar-sounding names?”

On the outskirts of Maing village, there it was, written on the side of a shed: Manuland.

I drove right by it at first. Its significance to the quest I’d just casually embarked upon didn’t register. “Wow,” I thought, when I realised Manuland’s import. “The Holy Grail!” The potential meanings of that sign stirred something inside me. I reversed my car to take it in.

“I don’t know what this means. I had asked for a signal of what’s connecting all these Man-sounding places,” I thought. “Now there’s an actual signboard! The Monde is definitely trying to tell me something,” I concluded. “Time to act!”

It was getting late. I photographed the shed. I checked into a nearby motel. I would tackle Maing properly the following morning.

That evening, as I was preparing to sleep, the idea of looking for an ultimate answer to the question of what binds these similarly sounding places wouldn’t leave me alone.

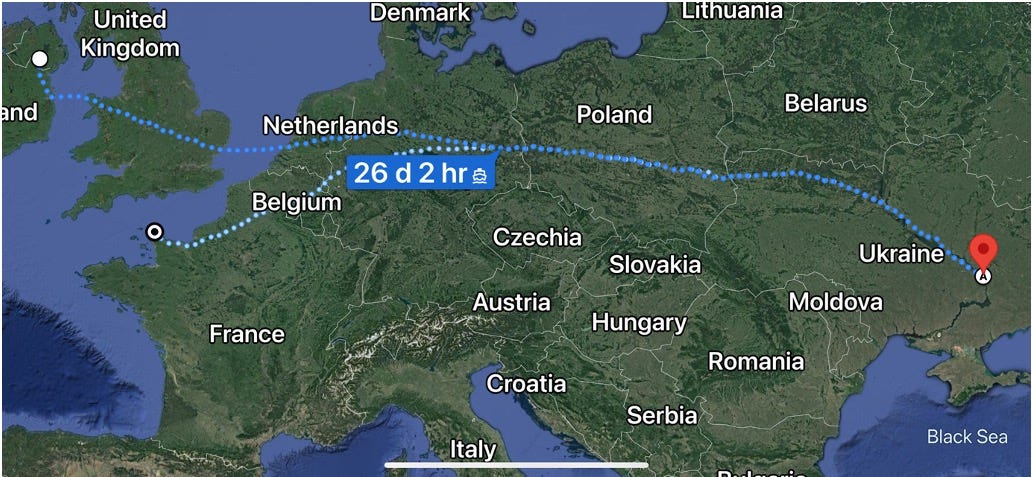

I was at the beginning of a three-and-a-half-thousand-kilometre journey from my home near Emain Macha to Ukraine’s third largest city Dnipro. Instead of just rushing back - driving for fifteen-hours-a-day for several consecutive days, as I had planned to… Perhaps I could drive a little bit more slowly? I could stop along the way, whenever I saw somewhere with one of these similar sounding designations.

I could try to find similarities between them – I could see if Manuland - an imaginary community radiating around the hub of the modern state of Ukraine and stretching from India to Ireland which I now had a name for- had any meaningful existence. I could dispatch the nagging notion that there might be a common meaning in Manuland’s ubiquitously similar sounding towns and villages, once and for all time.

So far during my diplomatic career I had found Man- sounding locales in many countries I’d visited.

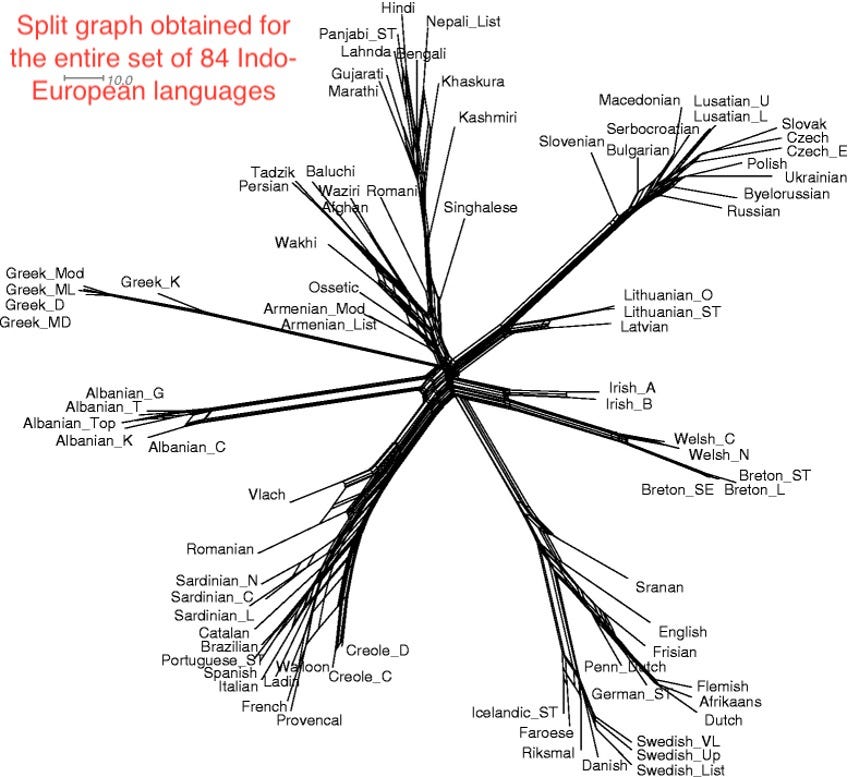

I’d noticed them in the contested borderland of India and China – Manirang Mountain near Mane Village in Spiti Valley. Spiti valley had been for thousands of years the historical boundary between the part of the earth where people spoke languages from what academics call the ‘Indo-European family’ and where they spoke Tibetan and Chinese. At the other end of the world, where we had also spoken Indo-European languages for thousands of years, there was Emain Macha, Ireland’s holiest site.

Now, I had a label for the previously unnamed space between Ireland and India: Manuland.

I still wondered what I could find out about why such similar sounding places existed so far apart, and at all points in between. It was a slightly crazy notion. If I could visit as many regions as possible with that Man-, Main-, Mon-, Men- sound in their names, then, perhaps, I could understand of what the essence of that sound consists, if anything?! Could I discover a hidden pattern? If I did locate any common thread running through these localities, maybe that would be the Manuland equivalent of the Holy Grail.

I had indeed been hunting for a new raison d’être, now that I had reached the compulsory retirement age of an Irish peacekeeping diplomat. Perhaps this quest for Manuland’s secrets could become my purpose as a retiree? Maybe it could fill the void I felt approaching me when in May 2022 I would be forced out of a job I loved.

First, I had to test if such a plan might work. The next morning, I doubled back with the aim of exploring Maing village. Could I find another augury there? Was there any other clue to complement the Manuland warehouse I’d glimpsed from the highway?

On my way into Maing, I noticed this scene: a signpost topped by a model of a horse drawing a plough bathed in the rising sun and framed by the gap between two trees.

It looked like a Bronze Age sun chariot racing across the sky. Right behind the sign was the stables of a riding school. Was Maing, something to do with horses’ manes? I’d recently learned the significance of the horse to the history of Manuland: In Ukraine, near where I lived, is the first archaeological evidence of a ritualised burial of a horse in human history. Then on a promontory of the Dnieper River at Dereivka, the first evidence in world history of the domesticated horse had been uncovered.

Many experts had figured out that the invention of a system for taming, exploiting and keeping horses was one of the seminal developments enabling the evolution of our modern human society. One of the first wheeled carts discovered anywhere had also been found close to the city where I lived. It had been ritualistically buried in the grounds of Dnipro airport around two-thousand-years before the first evidence of a chariot appears in ancient Greece. Knowing these facts, the idea of the horse’s significance in Maing (and perhaps even to its name) occurred to me that morning – but how interesting is that I wondered?!

I pressed on. I was looking for a sign the nature of which I didn’t know. Hopefully I would recognise it when I saw it, rather than a week later as often happened!

A road sign for a mediaeval church in the village provoked an obvious idea: the best place to start exploring new territory is its centre. Often old churches are the hub around which villages radiate. So, a means I’ll employ throughout Finding Manuland is to start at the centre of the hub. There’s abundant evidence that pre-Christian religious sites, such as wells and assembly places, were claimed by early Christian authorities. It was a means of annihilating the past and demarcating their new territory.

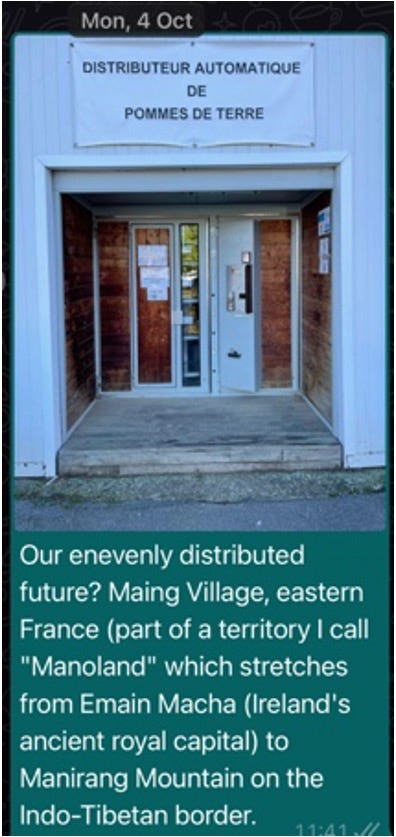

After parking near the church, which might well have been an ancient gathering place, I passed a sight I’d never seen before: an ATM dispensing potato instead of money. Instead. Of. Money? Maing clearly was a very different world! When I looked more closely that first mad impression melted. I saw a coin slot. I messaged some friends in a chatgroup thus:

“Distributeur Automatique de Pommes de Terre: Our unevenly distributed future? Maing Village, eastern France.”

That was the first moment Finding Manuland. It was the introduction of the idea to others – in this case a group of friends and acquaintances. I wondered: Would they respond? I didn’t think then that an ATM for potatoes had anything to do with finding the essential meaning of Maing (I hadn’t then worked out how the word money, as well as its meaning, the word meaning and also the idea of meaning was connected to Manu, measure, mana, memory, power,… and that money was everywhere too!).

Yet, following the Man- sound (in this case by entering Maing) as a way of helping to decide where to go in unfamiliar territory might well work to uncover new phenomena. Would there be any pattern of meaning in the identification of such curiosities? Only one way to find out, I thought. I pressed on.

The village itself was lovely and old. I went for my daily run. This is a second method I’ll use throughout Finding Manuland to help explore the hamlets, villages and towns we visit. Starting at the church in the centre, I ran in ever increasing circles radiating from it, iterating as I went, going up streets, and eventually reaching the edge of town. As I ran up that hill out of Maing, along an ancient, cobbled road, I imagined centuries, perhaps millennia, worth of farmers and journeymen ambling along there on their travels to and from markets.

After about two kilometres, I reached a point that was close to the top of the world; a sign less crossroads at which point the road surface switched to concrete. There were fields as far as I could see in every direction. Then I spotted it – a mound.

In a flash I visualised the ancient Ukrainian migrants who had built it to mark the burial of their local monarch. Two hundred metres away! All around it sheep were grazing. I saw what appeared to be a shepherd or a farmer seated meditating at the highest point of the tumulus.

By then I had become a pseudo-professional ancient Ukrainian sepulchral mound assessor. So even as I was taking in the figure of the giant herdsman strangely sitting on top of it, my mind was wandering: was the barrow human-made or a natural outcrop, perhaps left over from a glacier millennia ago? I set out to investigate.

Moving closer towards the kurgan (as such mounds are named in Ukraine), I began to focus more on the farmer. He was Gulliver-sized or maybe that was just the light up there under the wide-open blue sky yielding such an image? I was pleased that the giant herdsman was looking in a direction away from the path I was on. Farmers aren’t usually happy to see random strangers walk on their land. I was careful to walk along the side of the field that separated it from the road.

I managed to get up into polite shouting distance of the giant herdsman before he noticed me. I tried to look as polite as possible as we greeted each other. He stood up and leaned on his staff before acknowledging me, in a friendly enough way. He was a giant.

“Good morning,” he said in French. “What are you doing here?”

“I’m trying to understand how Maing got its name?” I replied, like him, getting straight to the point.

“You need to go to strange Cassels,” the giant herdsman directed me, oddly. “Where the Menapii tribe lived. You’ll find it on a hill about forty kilometres in that direction.”

He pointed vaguely into the distance. I got the feeling that that was as much as I would get out of him. Besides, that was definitely a lead. I thanked him profusely. I ran back to my car in the centre of Maing. When the signal returned, I checked my phone for any responses to my Potato ATM text. There was a message from a Belgian friend who was in the chat group:

“You’re close to where my family is from. My grandmother lives in Cassels. If you pass by there, go say “hello!” She lives in a strange castle. She loves visitors.”

Continues:

so beautiful and charming. Love the title "Looking for Manuland"

Brilliant Steve, really enjoyed that. That picture of the sign at Maing, with the horse chariot and sun, is amazing. Phantasmagoria. I like the derive like method of finding the Church and running in ever-increasing circles from it. Looking forward to reading what happens in Cassells!