Double Deity: Meaning of Tuesday

Finding Manuland XII

Merely by saying “Tuesday,” we unconsciously invoke the intercession of the Germanic God *Tiwaz.

By pronouncing Wednesday, we’re subliminally calling for the mediation of *Wodhanaz.

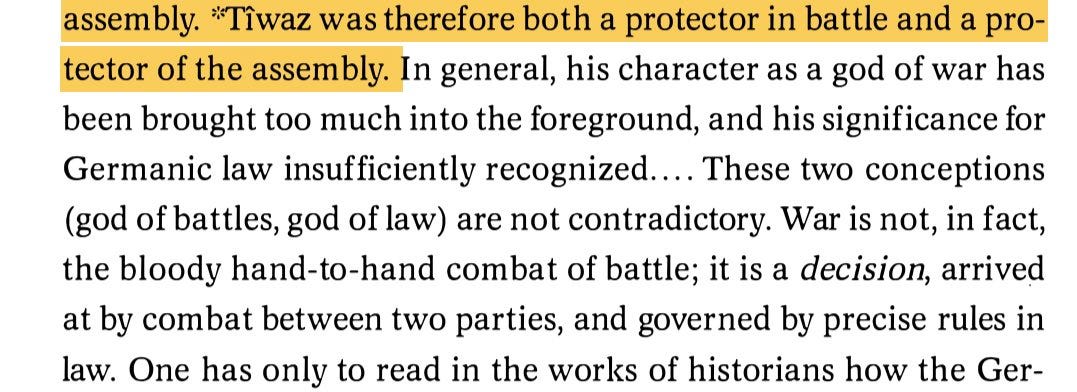

*Tiwaz and *Wodhanaz (and their equivalents in Italic culture – Mars and Mercury respectively) govern the operation of our free will; they’re our Gods of our sovereignty; our autonomy.

They also work on the level of our whole community. Decisions that rely on wishful thinking, on our hopes, our fears, our magical abilities to dream our selves’ alive, then, are within the ambit of *Wodhanaz. *Tiwaz, by contrast, governs rationality: effect following causes in knowable and predictable ways.

Usually, any decision we take, whether we’re leading a nation or just our own lives is a function of both Gods’ indulgence, to one degree or another. *Tor and Thor gave their monikers to Thursday. They look after warriors.

We appeal to Thor whenever we opt for violence in any of its manifestations - economic, physical, psychological or sexual. Friday is a memorial to *Freyja or *Frig which are the names of the pre-Indo-European God of fertility, farmers, the household.

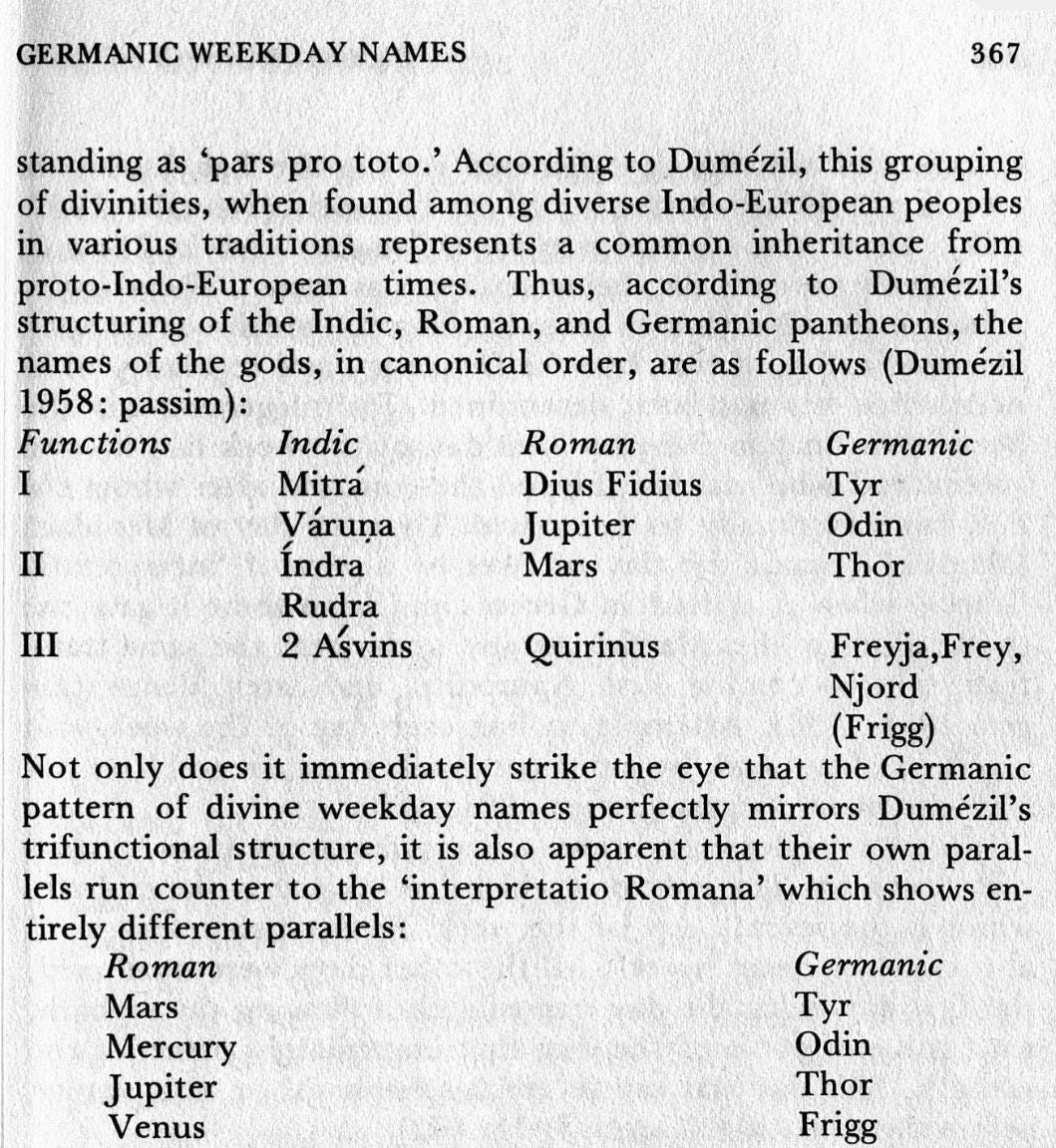

Each of these Gods - and the days of the week they’re memorialised as– are short-hand signs for vast systems of thousands of years of human culture across the entirety of the Indo-European cultural zone from Ireland to India.

We may not be aware of this (until you read Finding Manuland) but now you are, these signposts in our everyday conversation can unlock much to meditate carefully upon. Only one day – Friday- stands for a God which predates ancient Ukraine’s theological innovations (which innovations, as we’re about to explore, underpin all of Finding Manuland).

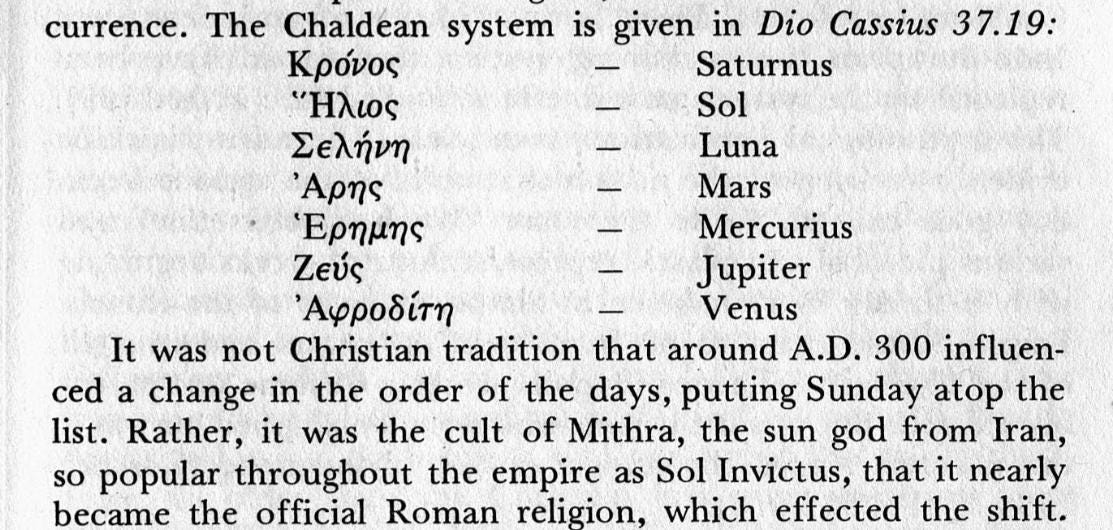

Christianity never managed to take ownership of the days of our week. This is a great weakness, from its perspective. Though part of Christianity’s unique selling point, from the standpoint of trying to make converts, was its rationalisation of many Gods into one. In Tibetan Buddhism, by contrast, adherents are expected to visualise dozens of deities as part of their daily practice.

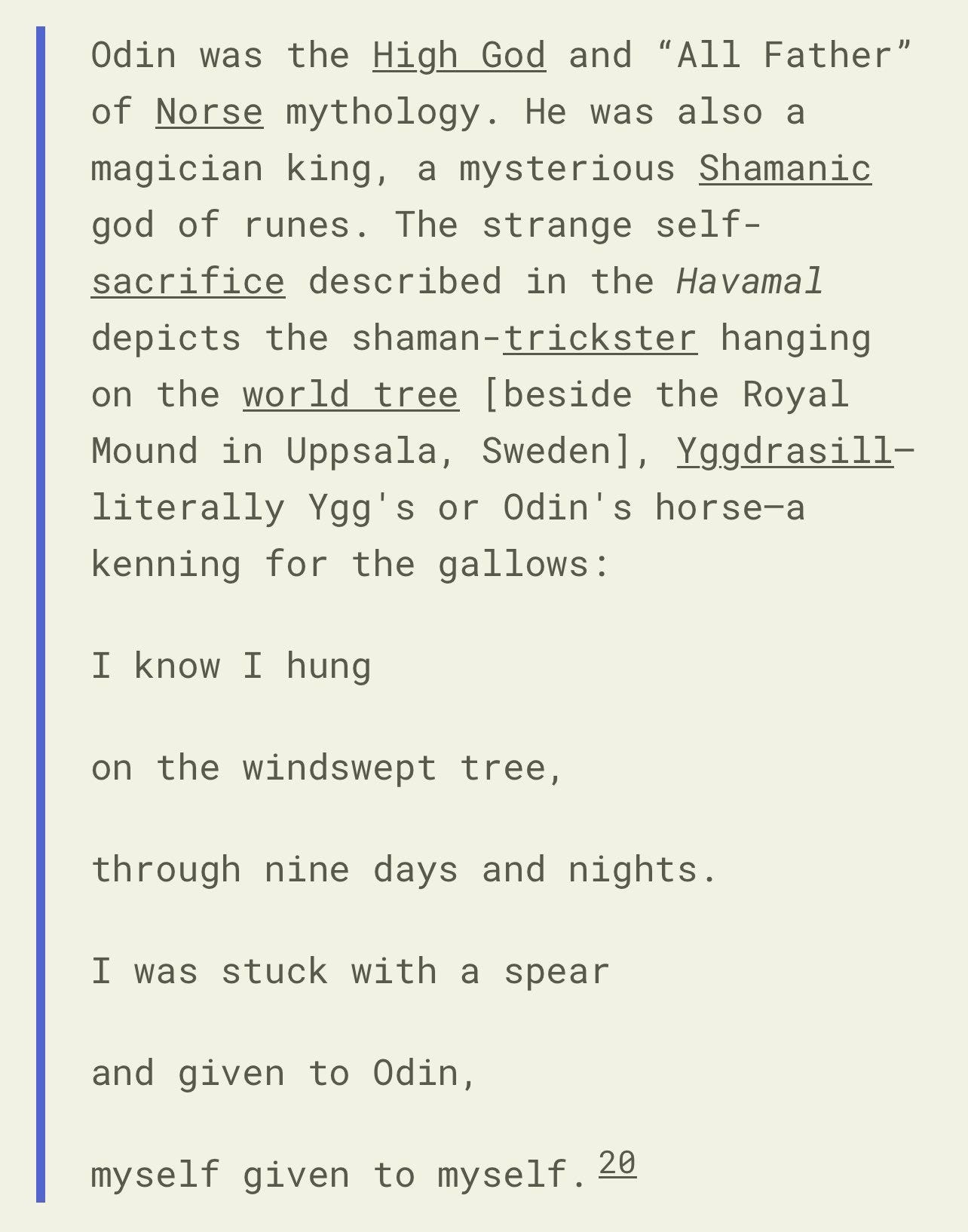

Yama, however, as Lord of Death (just like the variously named ancient Ukrainian God *Wodhanaz, Woden, Mercury, Varuna and Odin) is particularly important to Buddhists. The whole of the Buddhist practice is orientated towards helping Buddhists prepare for the moment this embodiment’s death process begins in earnest.

Anyone living with a cat who brings home mice or birds as offerings to their pet humans becomes quite familiar with death, unfortunately. Though knowing which mantras to use as poor creatures rescued from inside one’s pet’s jaws go through the death process is some compensation at least for my pain, if not theirs.

Hearing the word Yamnaya in the context of Ukrainian barrow-grave culture reminded me immediately of that Buddhist Yama.

I could not connect the two cultures, geographically separated by thousands of kilometres, as well as by several millennia. I hadn’t then realised that Christianity grew out of a Roman colony so that the Roman Catholic faith was an amalgam of influences, including the Italic culture of which it emanated. When I’d first heard the word Yama in that temple in Ulaanbaatar, Yama had seemed like an extravagantly exotic figure. I didn’t know then that the Buddhist Yama had evolved out of India’s first self-sacrificing king – also called by that unusual name: Yama. Early India’s Yama’s twin was Manu.

I hadn’t known that the Indian Yama had begun life as the recognisably similarly named Iranian God Yima. Or that there was a Norse God Ymir, who performed a similar role in that ancient religion as their near namesakes played in ancient Iran and India. Nor did I know that, as mentioned, Woden, another manifestation of the Germanic God *Wodhanaz (after whom Wednesday is named), had, like Yama, sacrificed himself. Woden, like Yama a Lord of Death, hanged himself from Yggdrasil, the cosmic ash tree as the foundational moment in Norse religion beside the three Royal Mounds in Uppsala.

Nor was I aware that in ancient Irish religion the land to which we go after we die was known as the House of Donn (Teach Duinn). According to the greatest scholars of Irish Celtic theology (Pokorny, Rees Brothers, Lincoln, Mallory, Carey) Donn is cognate with early Indian theology’s Yama.

“Cognate” means that a sound, word and/or its meaning has the same root; that, say, Yama and Ymir, which correspond phonologically (they sound alike), also complement each other semantically (they both have complementary meanings: they both died so as to guide us who come after them into the underworld), and they fulfil the same function (they operate as blueprints and guides for those who come after them).

Continued:

Continued from:

First in series: