Ancient Ukraine’s Don-sounding Rivers, Yama, and Lords of Death

Finding Manuland XIII

The similarity between the moniker Donn (Ireland’s pre-Christian Lord of Death) and the names of rivers which embodied Gods, Lords of Death and the passage to the afterlife across the Indo-European cultural zone may be significant.

It’s a structure that is immanent in foundational stories / myths / legend / religions across the Indo-European cultural zone. Therefore probably it is evidence of the Common Source culture in Ancient Ukraine (which forged the first Indo-European language, world view, religion and society).

Acheron and “Don’t Pay the Ferryman Until He Gets You To The Other side” and all that is simply a Greek manifestation of a reflex that spans the entirety of the Indo-European cultural zone.1

The American theologian Bruce Lincoln parsed the totality of Indo-European cultures’ accounts of passage to the afterlife.

Lincoln deduced what he took to be the Common Source story, and which, given the geographical origins of the first Indo-European language speakers close to where the Ruschists blew the dam probably originated around Zaporizhzhia and the Dniepr rapids destroyed by the Soviets to build the dams the Ruschists now keep trying to destroy:

“The picture that emerges is as follows. On the way to the otherworld, souls of the dead had to cross a river, the waters of which washed away all of their memories. These memories were not destroyed, however, but were carried by the river's water to a spring, where they bubbled up and were drunk by certain highly favored individuals, who became inspired and infused with supernatural wisdom as a result of the drink.”

It’s interesting that ancient Ukrainian territory and most of modern Ukraine is within the catchment area of the Don, Donets, Dnieper (Don Hyper), Dniester (Don Istris) and Danube rivers. I also note that the word the ancient Greeks (including Homer) used to describe the first Greeks who spoke an Indo-European language was “Danaans.”

OxfordReference.com states “Danaan” is “a word of unknown origin” – they haven’t yet made the connection between ancient Greek as an Indo-European language that was born in ancient Ukraine! I encourage Oxford University Press to get Finding Manuland!

Brilliant Armenian Indo-Europeanist Armen Petrosyan2 also noticed the similarity in sounds between the monikers of those aforementioned rivers in contemporary Ukraine, the moniker of the first Greeks - Danaans (as featured in Homer’s songs that were first created around 700 BCE about events 500 or so years earlier), the name of the goddess - Danu - for whom one of Indo-European Ireland’s three mythological founding tribes (tuatha de danaan) was named, the Welsh goddess Dôn, and the Dānavas, one of two families of Demi-gods (asuras) in very early Indian religion (dānavas = children of Dānu, who are believed to be the mythologised memory of migrants).

Petrosyan, writing a decade before the advent of archaeogenetics demonstrated that the first Indo-European language speakers emanated from the river valleys of Ancient Ukraine, came to no conclusion about where the first Dan- sounding monikered community emerged.

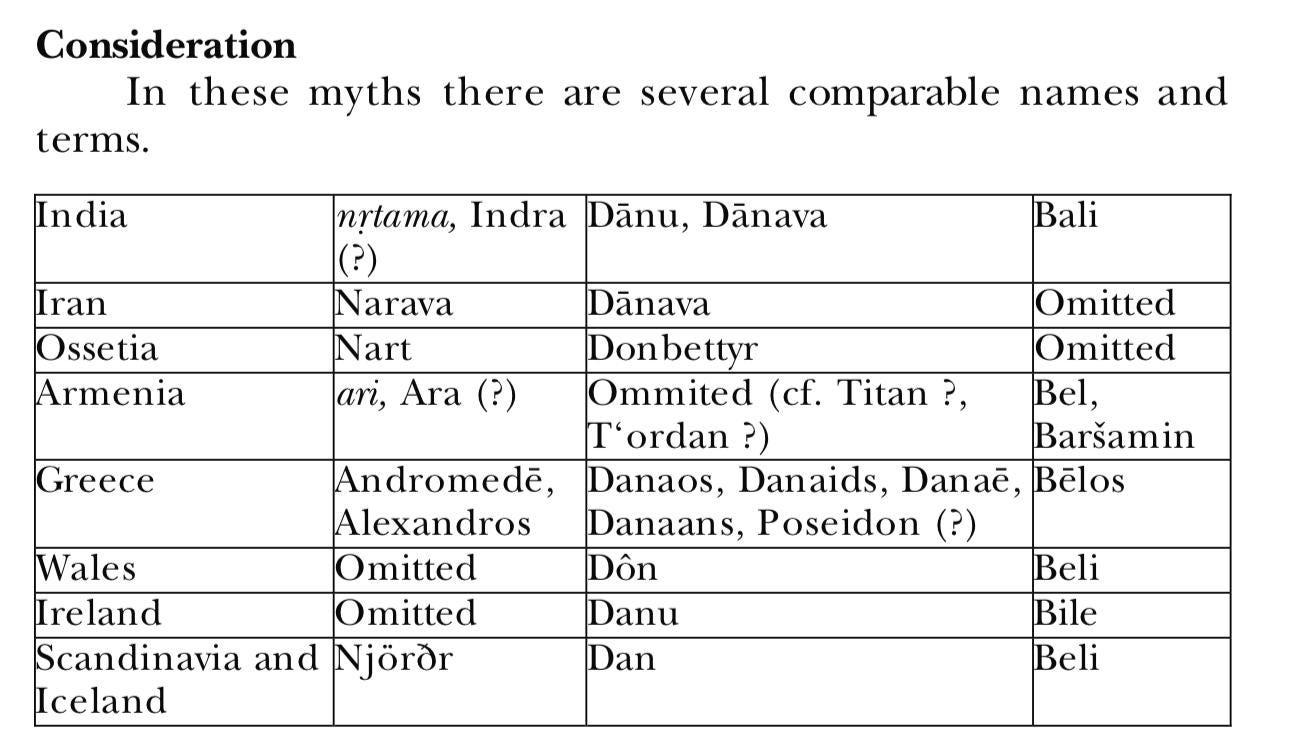

Petrosyan helpfully summarises the evidence in this table:

Petrosyan on the basis of inscriptions suggested, though provisionally, that the original Dan- sounding community may have originally lived in what is today Türkiye, in the city of Adana.

We have an inscription from 700 BCE:

Since that 2007 paper however genetic evidence demonstrates that the Yamnaya contain the DNA in equal parts of East European hunter gatherers and Levantine-Caucasians.

So it is indeed plausible that the Dan-moniker for the main God came from today’s Adana (which I plan to visit soon and report my findings here) where some of the Levantine-Caucasian community who would migrate all the way to Ancient Ukraine to contribute to the first Indo-European language’s creation lived.

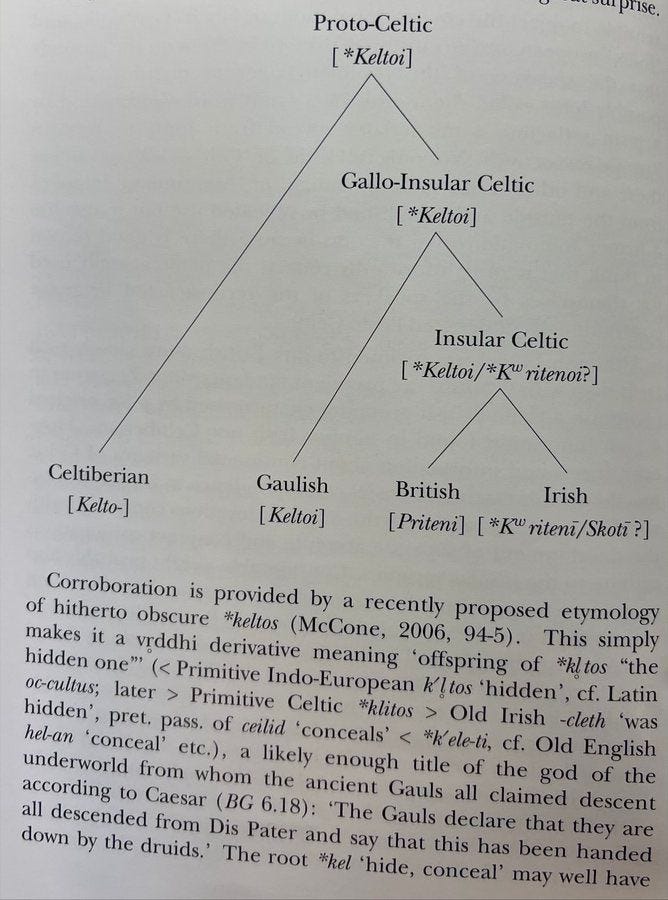

Naming whole peoples after the Gods they worship is extremely common – Christians, Buddhists, Belgians, even Celts are named for their founding characters –Roman commentators held that the Celts claimed descent from their monarch of death *Keltos (literally “the Hidden One” and an epithet for Donn, Indo-European Ireland’s first self-sacrificing monarch and Lord of Death).

Ancient Rome also took its name from one of its twin sacrificed founders Romulus (or vice-versa!), grandchildren of the deposed monarch Numitor. Romulus and Remus both get sacrificed in ancient Rome’s foundational myth.

Numa, Romulus’s successor, was a jurist (as distinct from the personification of a *Wodhanaz-like / Odin-like / Yama-like / Donn-like archetype whom Romulus characterises) credited with establishing Rome’s first institutions.

Numa, of course, as an anagram of Manu, is cognate with Manu (as is Numitor), India’s first lawgiver. Centuries later, Pontius Pilate, the Roman procurator of Judea who sentenced Jesus Christ to death on a wooden cross (thus igniting a world religion), survived self-sacrificing Christ’s death too.

The survival of Pilate’s secular rule after divine self-sacrificing Christ’s death is a story that’s been repeated at the root of Indo-European cultures since the first Indo-Europeans in ancient Ukrainian river valleys sang such structurally similar songs around moonlit cromlechs and burial mounds.

The echoes of these tales pop up again and again over the millennia, like trolls, in stories still told today (including in Finding Manuland) about Manu (India), Manyu/Mainyu (Iran), Manannán (Ireland), Manawydan (Welsh), Manuiscihr (literally “seed” or “son” of Manus in ancient Iran (named for Aryaman, who would become Yama in India and Tibet)), Menua (Armenia), Magnus (Scandinavia), and Mannus (German).

When you learn that the word in modern English “meaning” itself is a cognate of Manu, and that “name” is an anagram of “mean” (as in “signify”) and “mane” (as in “mound” and “horses’ neck”), then, the enigma underlying India’s first law giver and sacrificed Manu and his twin India’s first self-sacrificing king / Lord of Death Yama in the Rg Veda (songs first written down around 1,000 BCE in India and the basis of the Vedic religion of Ancient India), as well as their persisting mysterious roles in our culture, intensifies.

Finding Manuland identifies these manifold perplexities for the first time, explores them, and offers a resolution that I arrive at through scientifically acceptable means.

By the time I encountered Lord Yama, ancient India’s lord of death who most prominent Indo-European scholars (John Carey, Dumèzil, Puhvel, Kuno Meyer, Brinsley brothers, Mallory, Gimbutas,…) believe is cognate with Donn (meaning: despite the different monikers in different cultures they are signifying the same fundamental deity) for the first time in that warm temple in Mongolia in 2014, he had evolved out of his original role as Manu’s twin in early Indian religion.

Tibetan Lord of Death, Yama, like Saint Peter in Christianity, is visualised as sitting in judgment on which fate Buddhists deserve as the effect of their actions (karman).

Yama marks the result of our karma as we’re going through the death processes using white stones placed in a pile to represent all our good actions, while each instance of negative karma is symbolised by a black stone that Yama places in another mound.

Cairns of white mani stones – called mani walls – which are found across the Tibetan Buddhist cultural zone in villages and at high points echo this visualisation of Yama’s means of recording positive karma.

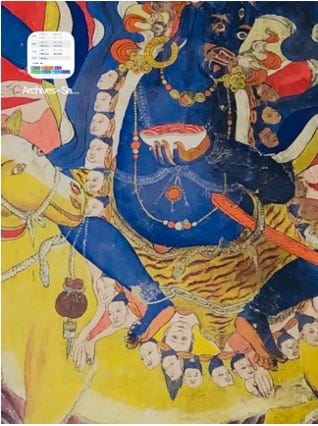

Yama’s often represented in ancient Tibetan monastic art as standing on the skulls of those who have negative karma (any action that results in suffering).

Here’s a photograph I took of a Yama-like painting in a monastery I visited in India, close to Tibet’s border and Mane village, in the autumn of 2019, just before Covid transformed our world, and gave me the space to discover Manuland.

While all of that explains why learning about the Yamnaya’s existence immediately caught my attention, lets rehearse again why the Yamnaya are of universal significance.

Continued:

Continued from:

First in series:

See especially Waters of Memory, Waters of Forgetfulness (Bruce Lincoln (Fabula; Jan 1, 1982; 23, 1))

PETROSYAN, Armen. “The Indo-European H2ner(t) -s and the Danu Tribe: The Deep History of Stories.” Journal of Indo-European studies 35.3–4 (2007): 297–310. Print.