Old Europe’s Pre-Indo-European Female Worshipping Culture

Finding Manuland XXV

In Europe and in parts of Western Anatolia, Ancient Ukrainian Indo-European culture replaced the more egalitarian culture of a period known to archaeologists as Old Europe – 6,500 - 3,500BCE.

We know of Old European (i.e. pre-Indo-European / pre-4,000 - 2,500 BCE) culture mainly through the work of American linguist and archaeologist Marija Gimbutas.

Today, virtually every paper in Cambridge University Press’s recent magisterial collection of state of the art papers from the foremost Indo-European linguistic, archaeological and bio-genetics’ scholars entitled “Indo-European Puzzle Revisited” inculcates implicitly or explicitly the general contours of Gimbutas’s findings from before the ancient DNA revolution of 2015. That Gimbutas was female in a mostly male field led to decades of gender-related dismissals of her top-notch scholarship.

For example, today’s foremost expert1 on the Anatolian language branch of Indo-European family begins his chapter in the The Indo-European Puzzle Revisited:

“Since the so-called “Ancient DNA Revolution” of the past decade, which has yielded many new insights into the genetic prehistory of Europe and large parts of Asia, it can no longer be doubted that the Indo-European languages spoken in Europe and Central and South Asia were brought there from the late fourth millennium BCE onward by population groups from the archaeologically defined Yamnaya culture.

“We may therefore assume that the population groups bearing the Yamnaya culture can practically be equated with the speakers of Proto-Indo-European, the reconstructed ancestor of the Indo-European languages of Europe and Asia, and that the spread of the Indo-European language family is a direct consequence of these migrations of Yamnaya individuals into Europe and Asia…”

It was Professor Gimbutas who first worked out the chronology of Steppe migrations west of the Don River. She was able to do this by stratifying archaeological finds in many dozens of archaeological sites between Ukraine and Ireland that she had personally worked on.

We also know of Old Europe through the archaeological finds in hundreds of sites from Ukraine to Portugal and particularly through sacred objects recovered. These finds point to a remarkably unified culture from West Anatolia to the west of Ireland. Old Europe lasted around 3,000 years, until the Ancient Ukrainian Yamnaya began their migrations from the area west of the Don River around 4,100 BCE - when as we saw in the last episode the cultural ancestors of the first Anatolian Indo-European language speakers had left Ancient Ukraine - until 2,500 BCE when the genetic ancestors of today’s Europeans had mostly left Ancient Ukraine to migrate westwards.

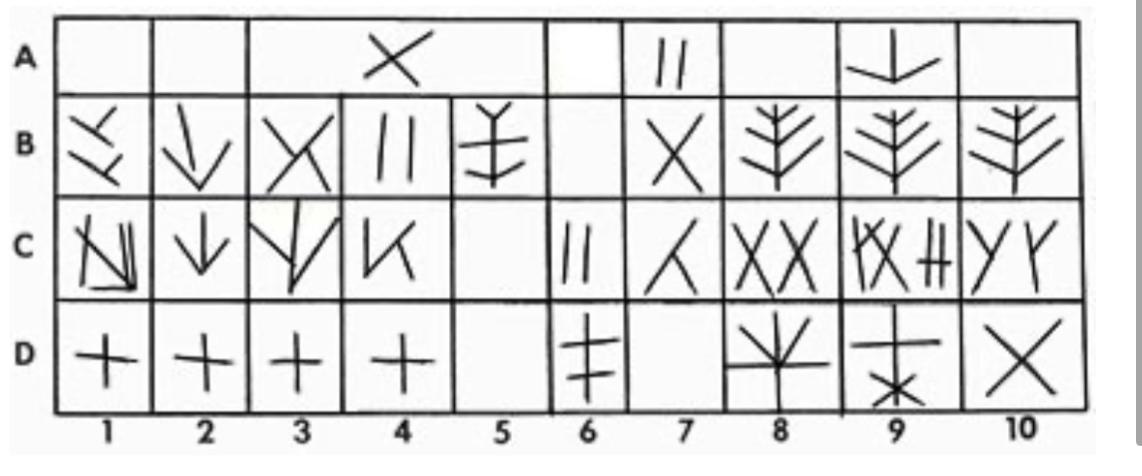

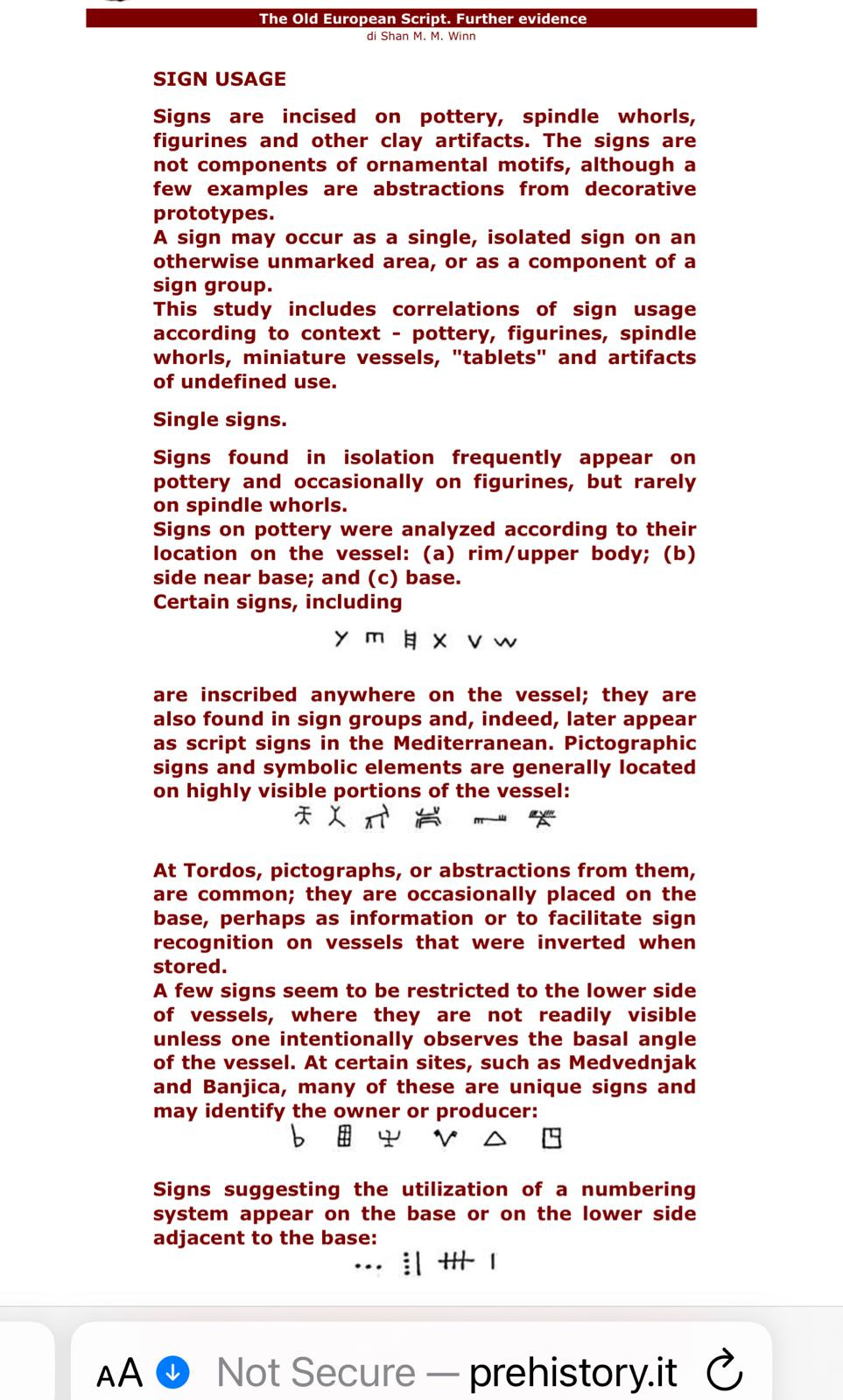

Old Europeans appear to have had a system of writing.

(See: http://www.prehistory.it/ftp/winn2.htm)

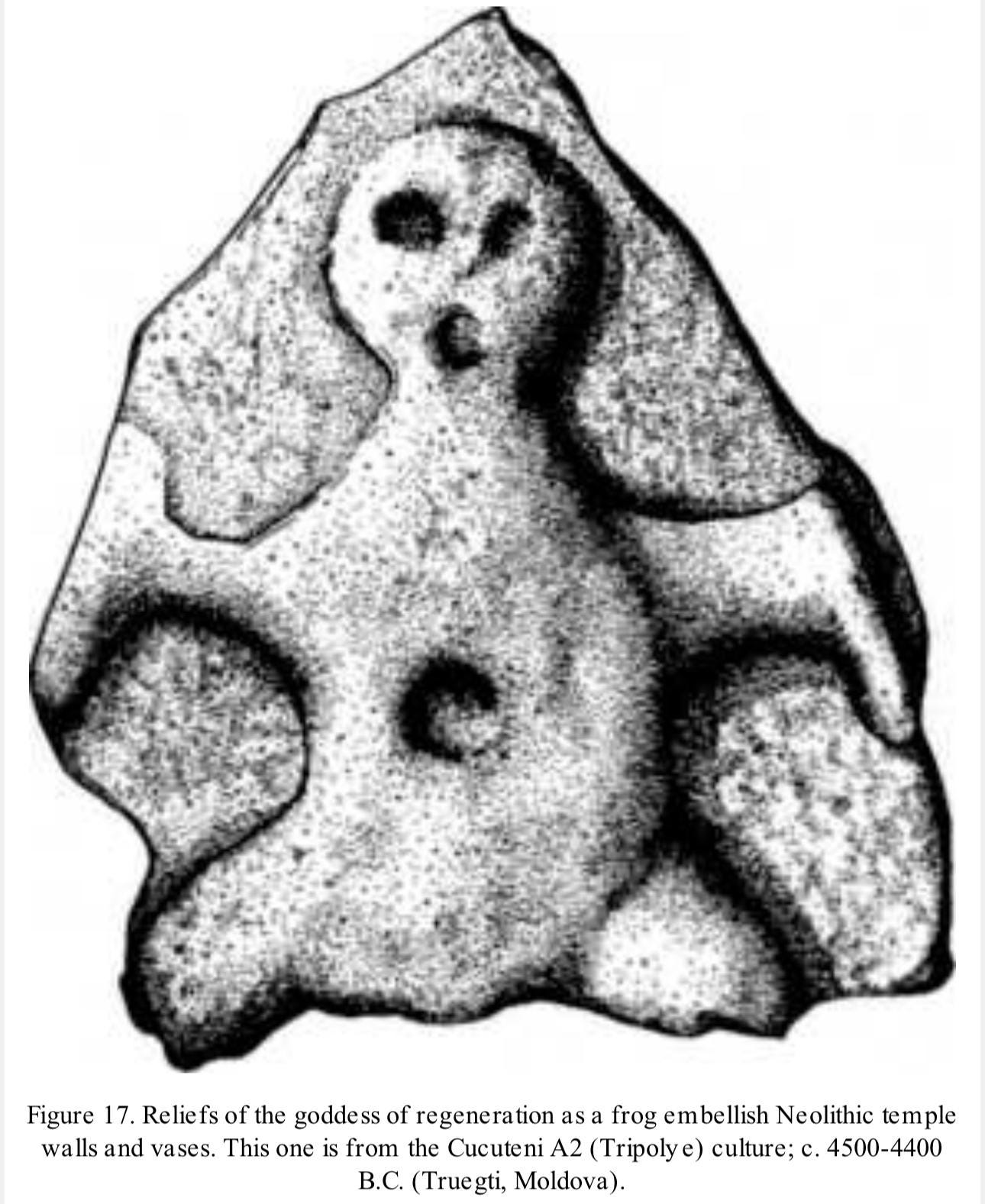

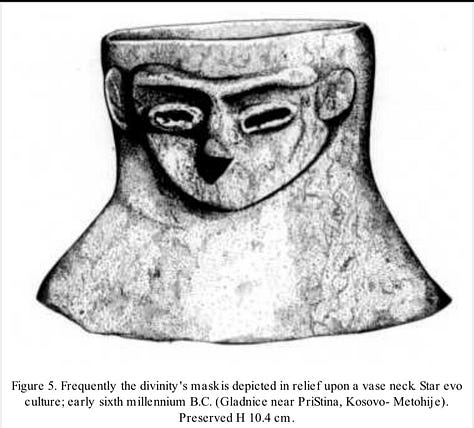

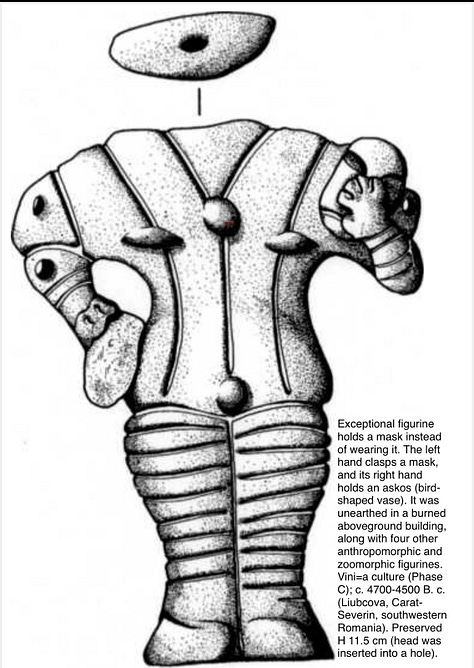

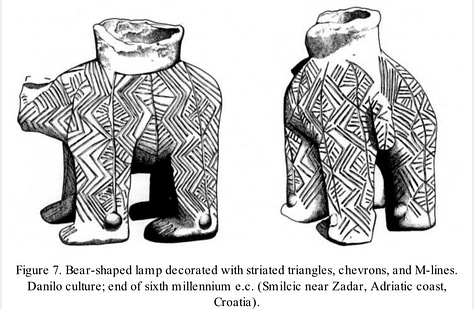

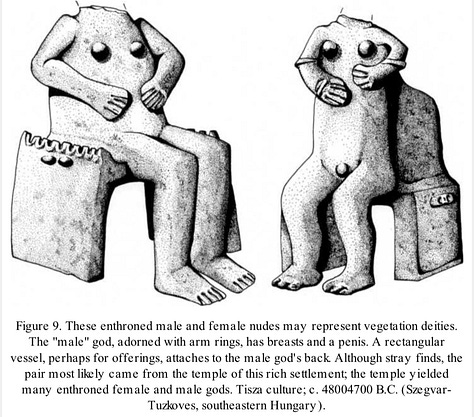

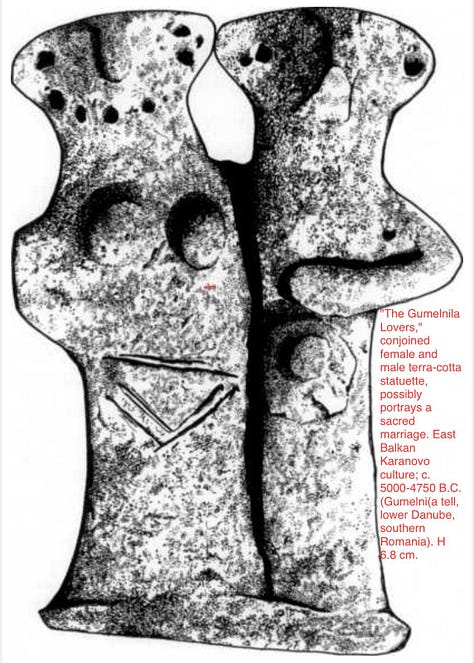

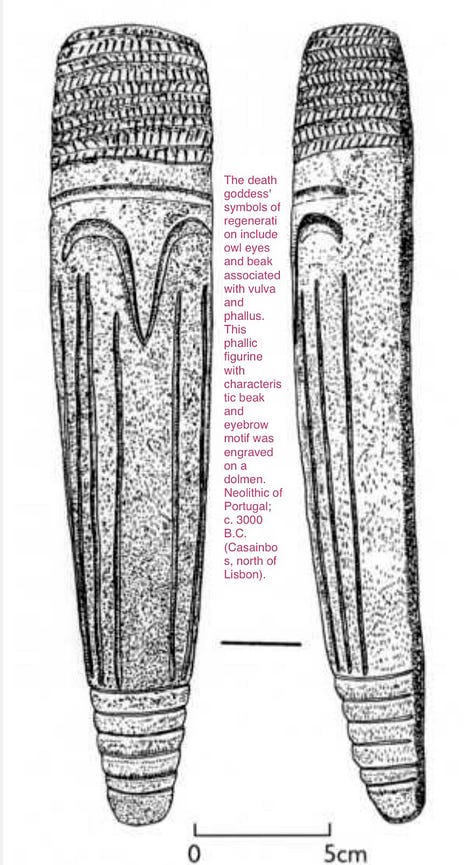

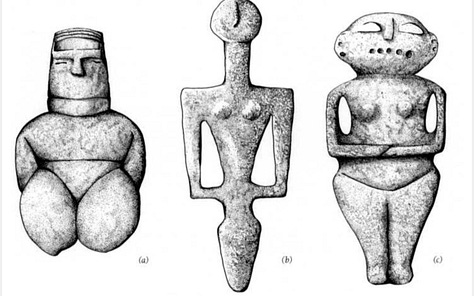

However, as yet no-one has been able to wholly decipher its script and its meanings. However, according to Marija Gimbetas’s findings 95% of statuary found in Old European sacred sites from Ukraine westwards as far as Ireland and Portugal is representations of female form.

We know Old Europe was more egalitarian than ancient Ukrainian because people in settlements were all buried together.

In ancient Ukraine, however, when the first Indo-European community the Yamnaya emerged, according to an abundance of archaeological evidence, they ascribed a male identity to their god – *deiwós.

If that word seems familiar, then it is!

That ancient Ukrainian word comes from *dei- ‘to shine’ and it belongs to the oldest Indo-European lexical heritage. It is the only common term that can be reconstructed in the field of religion.

You don’t need to have a PhD to see the similarities between the ancient Ukrainian sound and word for god and the languages it influenced:– deus (Latin), dio (Italian and Spanish), dieu (French), dia (Old Irish), dievas (Lithuanian), sius (Hittite), and deva (Old Indian/Sanskrit). According to Mallory and Adams’s concise summary of the totality of scholarship about these matters2:

“The basic word for ‘god’ in Proto-Indo-European [ancient Ukrainian] appears to have been *deiwós, itself a derivative of *dyeu- ‘[solar] sky, day’ [which itself came from] *dei- ‘shine, be bright’.”

Ancient Rome’s supreme God Iuppiter (Jupiter) and the ancient Indian God Dyāuḥ pitā are derived from the ancient Ukrainian for “sky father:” *Dyēus pətḗr. Zeus ancient Greece’s supreme God (and the son of Europa) is also a reflex of this ancient Ukrainian meme: the sound of “*deiwós” and Zeus is identical if you say them out loud (in either a Greek or Ukrainian accent especially). Zeus’s full name in the mythological record is Zeus Pater (Ζεύς πατήρ): the form; the meaning (the personification and deification of a universal principle that generates and governs) and the maleness of the universal principle personified are all indications of cognateness.

When Christians say “He” of their god, unknowingly, they’re channelling ancient Ukraine’s innovation of a supreme male God to reflect their (then novel) wholly male-centred mode of social organisation. The whole meme (sound, form, meaning and function) comes as a barely evolved package over thousands of years directly into today’s everyday speech across the whole of Manuland, from the very people who built that stone circle in Dnipro.

It’s useful to remember that Christianity grew out of a Roman colony where Roman patriarchal cultural memes, whose origins can be traced back to ancient Ukraine, were being promoted.

It’s simply amazing to think that lying underneath every use of the word “God” by a Christian lies the bedrock of a signifier the ancient Ukrainians who built the Dnipro cromlech used to signify the universal protector and generator of the day (literally: the father of the bright, solar sky).

Who then would have imagined such an auspicious trajectory for the sound, form, meaning and function of a meme they’d forged, through a little bit of semantic spread (courtesy of two-thousand-years of Roman, Greek, Christian, Hindi, Buddhist and Zoroastrian theology!) over millennia until today?!

Archaeological, linguistic and cultural evidence that pre-dates the Yamnaya migrations and the introduction of the first Indo-European languages across Europe shows that in Old Europe’s religion and culture, women played at least as important a role in ruling, as men.

By contrast, between when the first Yamnaya mane were built and that Soviet-era communist collective farm manager who was buried in the Dnipro tumulus in 1932, not much has changed in the patriarchal organisation of our societies!

Archaeologists can trace incursions of Yamnaya into Old Europe’s settlements, according to the evidence of the modes of burials, including the qualities of the artefacts buried with those whose graves are preserved in mounds. Finding Manuland will visit the communities across Europe to look for evidence in today’s world of these migrations in the places we now know the Yamnaya tribes settled after they left ancient Ukraine on their migrations.

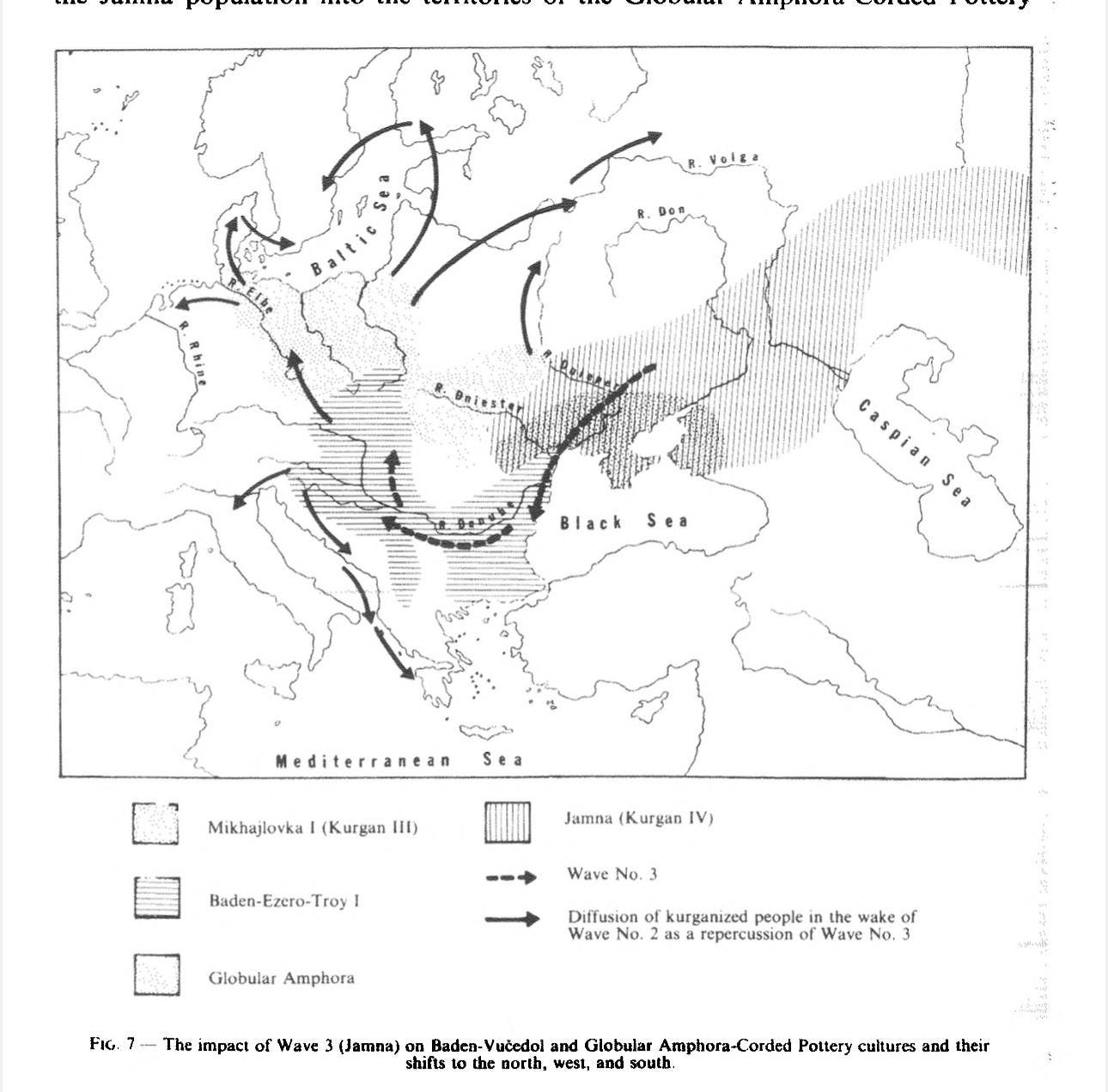

For example, here are maps included in Gimbutas’s early work on Yamnaya / Indo-European migration vectors. They show the routes of the three phases of Indo-European migrations across Europe. She first published what was then known as the “Steppe Hypothesis” in the 1960s, decades before the 2015 Nature journal paper that launched the Archaeogenetics revolution.

Gimbutas’s findings were based on archaeology, linguistic, and comparative analysis of mythology / religion in ancient communities. Now, since 2015, since the advent of archaeogenetics and isotopic analysis, Gimbutas’s hypothesis has been proven (by analysing isotopes in, say, teeth, scientists now can often determine the geographical location of the source of food consumed by those ancient humans while their teeth were being formed - this is how we now know the Yamnaya lived between the Don and Don Hyper (Dniepr) rivers of Ancient Ukraine).

Finding Manuland will use many such maps and means of finding the places where ancient Ukrainians settled during their migrations into every land forming part of every country of modern Europe:

As mentioned, one perennial custom of ancient Ukrainians which infused cultures across Manuland is the burial of people in a crouched position, inside a pit, covered with red ochre, with sacrificed animals, and set under an earthen burial mound.

Before ancient DNA could be used, these archaeological factors were the proxies that identified, for example, the island of Britain’s Beaker People with their ancient Ukrainian forebears.

There is a period in the archaeological record occurring at different moments in different parts of Europe when statues of female deities are no longer buried as mantic offerings. During this moment still visible in the archaeological record, whole communities are no longer buried together in undifferentiated graves. High kings are buried alone, as under the Dnipro mound whose destruction in May 2021 by greedy property developers motivated Finding Manuland and caused me to discover the Power of Mana. That’s the instant when it is presumed ancient Ukrainians’ customs replaced those of Old Europe in particular communities. The Dnipro cromlech was an Old European creation by the Stedni Stog culture. Then the first Indo-European Yamnaya buried the cromlech in the Mound.

Finding Manuland focuses on travelling to areas around Europe between that moment and a time when the ancient Ukrainian Yamnaya infiltrators become identifiable in particular zones of Europe as, say, Celts, Germans, Latins, Balts, etc.

Finding Manuland takes several characteristics of ancient Ukraine – for example, the ancient Ukrainian language spoken there and certain persisting burial customs that we know were first found in the river valleys of Ukraine - as threads to follow. We look specifically for their traces across the Indo-European cultural zone, in every modern European country’s archaeological record.

Our starting point is the fact that across the Indo-European cultural zone we speak languages that were forged in the crucible of eastern Ukraine. Finding Manuland focusses on the other reminders of these ancient migrations in today’s world. To achieve this goal, Finding Manuland takes its reader along with its author on mental and physical journeys throughout contemporary Europe and West Asia.

Finding Manuland is particularly interested in an early moment during the period misleadingly referred to as “prehistory.”

There was a moment, whose remnants Finding Manuland will seek out in our contemporary world across Europe between when ancient Ukrainians were just mere Yamnaya and when they had transmogrified over millennia into Celts, Germans, Balts, Slavs, Greeks, and Italics.

There are oodles of texts focussing on the Roman documents that elucidate the other ancient Ukrainian tribes. Finding Manuland reframes all of those peoples as ancient Ukrainians and, originally, seeks out the moment in the archaeological and cultural record in modern European states when ancient Ukraine met Old Europe.

For example, the Etruscans were part of Old Europe. They managed to resist cultural conquest by the ancient Ukrainians, in a way the rest of the Italic language speaking tribes in Italy didn’t - the Etruscans kept their own language, mode of social organisation and religion until the ancient Roman Empire conquered them. By the time Rome had folded all of the Italic-language speaking tribes into its empire, the Etruscans were still distinctly an artefact of Old Europe (as the Basques, Estonians, Finns, and modern Hungarians are still to this day, at least linguistically). So, in Finding Manuland’s Italy chapter the contact and eventual conquest by the Romans of the Etruscans is what will be our elucidating focus.

As we travel into and through most other European countries, we will visit the places archaeologists now know where the ancient Ukrainians first settled. I will tell the story of the moment between when the ancient Ukrainians arrived and when they had become the Greek, Roman, Celt, German, Norse, Baltic and Slavic peoples. I will chart that network of ancient migrations by the people who buried their dead kings under mounds, crouched at the knee, with ochre and other manifestations of ancient Ukrainian customs. I will tell the story of how the Basques, Etruscans, Finns, Estonians and modern Hungarians resisted being assimilated by ancient Ukrainian migrants with their new-fangled technologies of the domesticated horse, wheeled carts and patriarchal mode of social organisation.

Much of the archaeological, linguistic and mythological evidence for this story has only become available over the past couple of decades. No-one has told this tale before in the form of a travel book. Alas, the great American archaeologist, linguist and comparative mythologist Marija Gimbutas did not live to see ancient DNA evidence prove the truth of her “Kurgan Hypothesis” – the idea that the homeland of all the Indo-European cultures was in the area of Ukraine where the Yamnaya first started burying their monarchs in mounds.

We’re most interested in following the material and cultural evidence across Europe of the descendent trajectories of the ancient Ukrainians who had left Ukraine before 2500BCE.

2500BCE is the latest date when ancient Ukrainian can have been spoken by the whole ancient Ukrainian Yamnaya people in ancient Ukraine. Using archaeological and linguistic evidence experts understand that after 2,500BCE the core ancient Ukrainian population had already splintered into the essential diverging, geographically separated groups whose linguistic and cultural innovations would gradually evolve over the millennia into what have become today’s 84 Indo-European languages.

The “Proto-Indo-European” language is how boffins describe what we’ll just call “ancient Ukrainian” – after all, if ancient Greek is known to us as ancient Greek and ancient Greek itself is a product of ancient Ukrainian then, why shouldn’t we re-brand Proto-Indo-European thus?! The conventional view among scholars today is that Indo-European languages were first forged in the river valleys of present-day Ukraine.

Don Ringe, author of Oxford University Press’s from Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic, expresses what we know for sure carefully:

“The earliest ancestor of English that is reconstructable by scientifically acceptable methods is Proto-Indo-European, the ancestor of all Indo-European languages. As is usual with protolanguages of the distant past, we can’t say with certainty where and when PIE was spoken, but evidence currently available points strongly to the river valleys of Ukraine in the fifth millennium BC.”

Continued:

Continued from:

First in series:

Mallory, J. P, and Douglas Q Adams. The Oxford Introduction to Proto Indo European and the Proto Indo European World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023. Web.